Creating public value in responding to domestic abuse

How can the police and agencies responsible for tackling domestic abuse connect with their communities and create public value in this area of work?

Written by Dr Linda Reid, Alliance Manchester Business School

There is copious research about the phenomenon of domestic abuse, but little that is written from a leadership perspective. This doctoral case study research examined the leadership of domestic abuse in the context of the police and their partners in a large city in the UK. Despite the fact that providing services to vulnerable members of the community is a multi-agency responsibility, little is known about the leadership responsibilities to activate community support.

Leadership and domestic abuse

The real issue of domestic abuse is a social issue, and the responsibility of society at every level. Rittel and Webber (1973) argue that societal problems are “inherently wicked” and that they are ill-defined, are never resolved, and rely on “elusive political judgement” for resolution, rather than tame problems which are clear and solvable. Domestic abuse is a wicked societal problem. Grint (2010) suggests that leaders cannot force people to follow them in addressing a wicked problem, because the nature of the problem demands that followers have to want to help, and that leadership is the art of engaging a community in facing up to complex collective problems. Brookes and Grint (2010, p.1) define public leadership as,

A form of collective leadership in which public bodies and agencies collaborate in achieving a shared vision based on shared aims and values and distribute this through each organisation in a collegiate way which seeks to promote, influence and deliver improved public value as evidenced through sustained social, environmental and economic well-being within a complex and changing context.

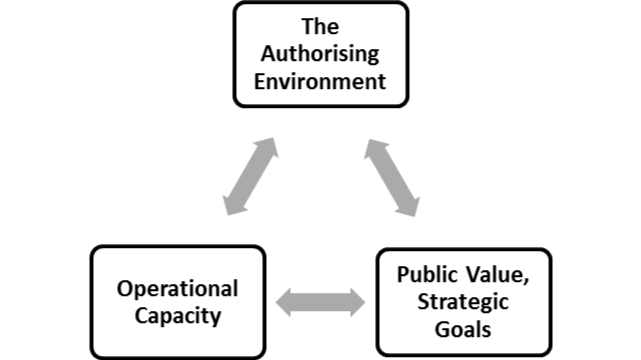

Moore (1995) describes a “strategic triangle” of three elements which must be aligned in order to develop a strategy in a public sector organisation: public value; legitimacy and support; and operational capabilities Figure 1:

Figure 1: The Strategic Triangle (Moore, 1995)

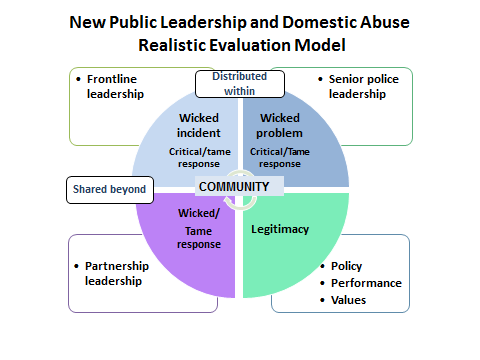

The operational capabilities are the assets and resources that are available to leaders; legitimacy and support is formal authorisation and resources to sustain the enterprise, together with the actors supporting and influencing the authorisation. Moore (2004) says that public sector managers have much less discretion to define the purposes of their organisation and the strategy to achieve them because they are subject to their ‘authorising environment’, which includes politicians and those who authorise them to take action, funding and resources. They are held to account for their performance and, in the public sector, authorisers include the elected representatives of the people, Police and Crime Commissioners and Mayors. In this research a model was developed to evaluate the extent to which a new public leadership approach has been adopted, see Figure 2:

Figure 2: New Public Leadership and Domestic Abuse RE Model

The community and domestic abuse are at the centre of this model, because it is the nub of the wicked problem and is where the value creation should be focussed. There is a tension in policing domestic abuse because the public do not always value police action that involves arrest or detention of the perpetrator, or a criminal prosecution, or even questions about their intimate and sensitive family relationships. On the other hand, police policies, driven by external influences which include academic and feminist critiques, insist on the use of positive police action, arrest and prosecution as a deterrent to domestic abuse.

According to Moore (1995) there are three tests that are necessary conditions for the production of public value:

- the need to scan authorising environments for changes and to determine what political mandate exists,

- to scan environments for emergent problems,

- to review operations in your own organisations and other similar organisations.

Measuring public value

The plethora of changes that have taken place in the national and local landscape, the introduction and politicisation of the Office of the Police and Crime Commissioner and Mayors, have created a complex landscape. Strategic leaders should be curious about the following:

- What is the public value proposition?

- What are we aiming to create?

- What is the legitimacy and support we need to achieve that?

- Which stakeholders need to be included, and who will support or oppose it?

- What operational resources do we need to achieve this outcome, and where will they come from?

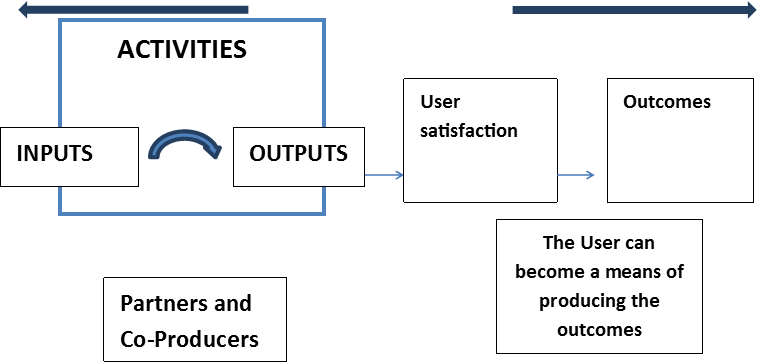

Ronald Heifetz (1994) views leadership in terms of adaptive work, and believes that leadership requires orchestrating the conflicts among and within the interested parties, to join the stakeholders together as a community of interests, so that they withstand the stresses of problem-solving. Benington’s model (2011) may be useful in defining the unit of measurement of public value as what the public values and what adds value to the public sphere. In public service organisations the creation of public value is often found at the front line, where there is direct interaction between workers, users and communities. Upstream policies and contextual factors influence these frontline relationships and processes. This model (see figure 3) focusses on the processes by which it is co-created and the outcomes.

Figure 3: The Public Value Stream adapted from Benington (2011)

Public Value Stream

The role of leaders in wicked issues is to ask the intelligent questions, such as:

At what stage in the process is public value clearly being added? Where is the positive contribution to the desired public value outcomes, and once identified these need support and resources?

At what stage is public value being subtracted or destroyed? Can these activities be re-aligned or removed?

What parts of the public value stream are lying idle or stagnant? What can be done to unblock the situation and mobilise new flow, energy and activity to achieve the goals?

Benington’s approach to identifying the creation of public value can be used in a domestic abuse context, integrating a co-creation model, where public value is added through the work of partnerships and networks. An initial consideration could look like this,

Figure 4 Domestic Abuse Public Value Stream – A Co-Creation Framework

|

Authorising Environment |

Public Value Strategic Goals |

Operational Capacity |

| Who is currently involved in this work | Have we set clear strategic direction | What resources can we currently mobilise |

| Who are the stakeholders | Have we set specific outcomes | Are they sufficient |

|

Had sufficient authorisation been mobilised

|

What does the public value | What operational resources are required to create the identified strategic outcomes: funding, expertise, systems, leadership, accountability, technology, equipment and estates |

| Have we created diverse coalitions and partnerships across the public, private and community sectors | What will add most value | Where can we get more resources |

| Where are the conflicts of values, interests and perspectives | What are the adaptive leadership challenges | Have we got the right people |

| Have we scanned the environment for changes | How can we build commitment to the strategic goals | Are our operational resources aligned to achieve our public value outcomes |

Many of the opportunities to create public value take place at the frontline of policing domestic abuse. In mapping the public value stream in the domestic abuse context, consideration needs to be given to the competing values and interests faced by frontline officers. They are at the interface of negotiating what the public wants, and what is best for the public, whereas Police and Crime Commissioners or Elected Mayors have a mandate from the Government to create public value within a fully inclusive community context.

In the context of the PCC framework and devolution there is currently no defined mechanism or model nationally to create the outcome of civic engagement. The Office of the Police and Crime Commissioner or elected Mayor could be the mechanism to orchestrate the competing values of partnership, strategic leadership, frontline leadership, and community engagement, to achieve effective service delivery outcomes in domestic abuse initiatives. Little is known about the mechanism that would engage perpetrators to achieve the outcome of preventing and reducing domestic abuse from being committed. Many victims are unwilling or unable to co-operate, or are too ‘hard-to-reach’ by current policies. The adaptive challenge is to work differently to add value for the community in tackling domestic abuse.

References

- Benington, J. and Moore, M. H., (2011) Public Value Theory & Practice, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan

- Brookes, S. and Grint, K., eds. (2010) The New Public Leadership Challenge. Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan.

- Grint, K. (2010b) The cuckoo clock syndrome: addicted to command, allergic to leadership, European Management Journal, Volume 28, 306 – 333, [online]. Available at: doi: 10.1016/j.emj.2010.05.002 (accessed 31 July 2015).

- Grint, K. (2010c) Wicked Problems and Clumsy Solution: The Role of Leadership, in Brookes, S. and Grint, K., eds. (2010) The New Public Leadership Challenge. Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 169 – 186

- Heifetz, R. A. (1994), Leadership Without Easy Answers, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Moore, M. H. (1995) Creating Public Value. Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Moore, M. H. (2013), Recognizing Public Value, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Rittel, H. And Webber, M. (1973) Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning. Policy Sciences , Volume 4, pp. 155 – 169, [online]. Available at: DOI: 10.1007/BF01405730 (accessed 20 November 2010).

Author

Dr Linda Reid

Dr Linda Reid

MSc., BA (Hons), Cert. Ed., M.CIPD, PhD.

Associate Tutor NHS Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and Nye Bevan leadership programmes, Executive Education Associate Tutor.

Professional profile

Linda is an associate tutor for the NHS Elizabeth Garret Anderson (EGA) MSc programme at Alliance Manchester Business School (AMBS). Anderson is a blended masters learning programme of leadership development for mid to senior level leaders. She is also a learning set advisor on the Nye Bevan programme, a leadership development programme for aspiring executive board level leaders.

Linda was a Visiting Research Fellow at Alliance Manchester Business School from 2010 and completed a PhD in leadership in 2017.

She was a police officer for 25 years and retired as a Detective Chief, Public Protection, in 2014.

Note: N8 PRP blog articles give the views of the author(s), and do not always reflect the views or position of the N8 PRP, nor any of the partner organisations.

0 Comments