Improving policing research and practice on child to parent domestic violence and abuse: Reflections on the day

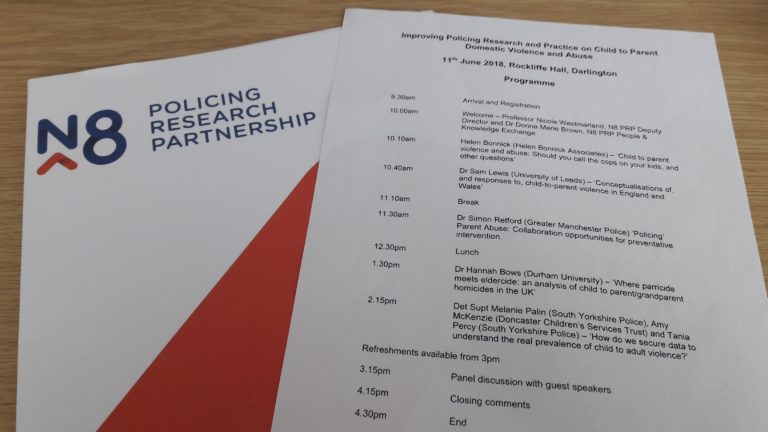

The N8 PRP recently hosted its annual Knowledge Exchange conference and this year focused on the theme of Child to Parent Violence (CPV).

The N8 PRP recently hosted its annual Knowledge Exchange conference and this year focused on the theme of Child to Parent Violence (CPV).

In this article, Tania Percy, Manager of the Performance Management Unit in South Yorkshire Police, gives her reflections on the days events and outlines what each speaker presented.

It is a strange concept, discussing the harsh reality of child on parent violence (CPV) within the beautiful backdrop of Rockliffe Hall in Darlington. Yet there we were, a room of 60+ academics, self-confessed ‘pracademics’, and multi-agency partners all with a professional interest or expertise within this area.

In welcoming all to the conference, Professor Nicole Westmarland summarised the key issues faced by academics and police alike into one central question – How well can we collectively understand this complex area given it is largely hidden within the wider banner of domestic abuse?

Defining child to parent violence

Defining CPV is a fundamental question for those working and researching in the field. By current definition the victims and offenders of domestic abuse are over 16 years of age. As a result we find much of the focus precludes the circumstances of interfamilial child to adult violence which can begin at an early age.

Simply defining this area as CPV caused some issue for the attendees, with acknowledged concern for those carers/grandparents within household relationships which may fall under the banner of people to whom children would look to exert control over. Additionally where the violence is sibling on sibling, is this any less of a concern from a child violence perspective? The focus on definition by age limitation was considered a barrier, and more so when we consider the input from Dr Hannah Bows with a focus on parricide and particularly eldercide (victim over 60 years old).

An interesting post-conference discussion on holesinthewall.co.uk by Helen Bonnick cites the ‘eyebrow raising’ suggestion from Dr Bows of whether a definition was even necessary to progress understanding of CPV, or if the focus of intervention should be made on the basis of risk and harm parameters. Rather than repeating this article, I would encourage those interested to get involved in the discussion!

Why is understanding CPV so important?

Is this a puerile question? I’d say not. It is clear that the framework around domestic abuse which incorporates much of CPV is necessarily wide, but this over time has led to recording practices, funding streams, policing resource and academic focus largely around Intimate Partner Violence (IPV). So this area is comparatively lacking in joined-up focus across agencies and consequently the intervention opportunities are not well established.

Helen Bonnick referenced within her presentation, ‘Should you call the cops on your kids, and other questions’, how CPV has experienced changes in focus within the last 10 years. Research studies in the 1980s were the first to try and estimate the levels of CPV in society, showing how relatively ‘young’ this area is and that prevalence largely remains best guess. We also know the results from several academic / policing research papers appear to be highly gendered (male child to mother) so could it be that we are failing to recognise the extent of other CPV, with an over-representation of samples within CJS outcomes datasets? We also know that much of it goes unreported. Unsurprising as parents often consider the wider outcomes of the involving support and CJS agencies on the wider family unit.

So if we don’t fully understand the prevalence, how can/do we deal with it?

Helen reported against her work in mapping the UK intervention support agencies for CPV, and these, albeit not complete, showed the ‘post-code lottery’ of support for both the children and the parents. Dr Sam Lewis also highlighted one of the common issues of CPV is it being seen as a ‘parenting issue’, with limited options considering the reality of the parent as the victim and offering support accordingly.

During the Panel Discussion session a concise question was raised from the audience – ‘what happens if tomorrow my child hits me with a baseball bat, what I should do?’ The panel discussion considered the reporting to police, but in terms of intervention, the concern was that the pathway to finding alternative support may not be consistent in availability or response.

There are clearly pockets of positive work across the agency spectrum and encouraging innovative approaches within multi-agency setting – Cleveland’s investment in Early Intervention workers was a point of interest to all. However, as the Home Office cited in the 2014 ‘The Information Guide: Adolescent to Parent Violence and Abuse’ (APVA), there is no one response to CPV/APVA. Within the conference panel discussion it was highlighted that the silo data systems, lack of incentive for all agencies, impact of austerity on agency thresholds and simply the issues around using personal data across multi-agencies present barriers to joined up working.

Factors linked to CPV cases

It is important to say that the risk factors were not considered for their causative relationship, but generally that research has focussed on the factors present within CPV situations. Dr Sam Lewis and later Dr Simon Retford from Greater Manchester Police looked to the wide range of factors present in cases of CPV, not exclusively but noted domestic abuse in the household, substance abuse, mental health, learning difficulties, ASD, parental boundaries, wider context around family dysfunction, adoptive relationships, attachment disruption and traumatic events.

In the afternoon workshop discussion lead by Det Supt Melanie Palin from South Yorkshire Police, it was interesting that the focus turned to the child’s developmental milestones from a very young age – with a definite focus on the importance of the first few years in identifying the factors linked with CPV. Some issues considered neurological, with the main focus on behavioural factors. This causes the CPV work some difficulties. If we look to where data capture is strongest currently, where academics turn for information, then it is largely police datasets where it is held with the requirement for capture (policing purpose) of the offender details and the nature of their actions. But, policing focus is on offenders over the age of criminal responsibility, and as a collective we can miss the opportunity for supporting early intervention with a range of partners, some of which have no requirement to officially document CPV / APVA concerns.

The young people engaged in early CPV may then be seen later in life to be linked to violence outside of the home. This may impact in the immediate circumstances on the household and all siblings / friends / support agencies linked to the family, but if no intervention is successful then the increased violence can impact more widely as a societal issue, and demand on agencies increase. Dr Simon Retford introduced some engaging case studies which demonstrated the need for strong multi-agency partnerships to support all those involved.

What options are there for multi-agency working?

Dr Sam Lewis and Dr Amanda Holt’s four-year programme on the ‘Conceptualisations of and responses to child to parent violence in England and Wales’ highlighted the concern between pursuing a criminal justice response to the violence, and not wanting to criminalise a child – with enforcement being seen around adolescence largely, and interventions not reaching the younger age ranges. This for me hits the crux of the problem for those of us sat within the policing world. In reality those involved in policing are yes, reacting to the situational harm we respond to daily but we are also trying to engage in those early opportunities to prevent enforcement being the only effective course of action available to us to deal with the risk and harm we are presented with at a later stage. The perception of policing interest in early intervention, and the extent to which the police can support early intervention may be difficult to explore with partners, victims and offenders for different reasons. Likewise, the parental perception of social care involvement can be a barrier to supportive intervention opportunities. But, there are examples where much can be achieved across multiagency groups in practice, and the presentations provided some good evidence of opportunities for multi-agency response.

Did we come up with a solution

Ok, rather disappointingly, but perhaps not surprisingly, there is no panacea. I’m not one for management jargon, but this does feel like we are ‘on a journey’, and if I would send any message out from the conference it would be this – we all want to achieve the same end, wherever in the ‘life-course’ we are working with the abused/abusers. That has to be a positive sign for the future partnership working, and to that extent it has for me fulfilled the brief of an N8 conference – fostering relationships to support the problems of policing within research.

The real positive I took from the experts attending was how widely recognised this issue is now becoming, and the clear willingness of those involved to engage with each other. The opportunity this presents for meaningful policy developments is apparent and important – and the focus for academics, pracademics and practitioners alike is that we now need a remit and agenda for which multi-agency platforms can deliver appropriate intervention linked to risk and harm.

Tania Percy is the manager of the Performance Management Unit within South Yorkshire Police, responsible for all statutory and corporate performance management and policy issues. Within this role she has a keen interest in embedding Evidence Based Policing in supporting process improvement within the force and represents the force within the N8 Policing Research Partnership..

0 Comments