Hands, face, cyber space: How the pandemic is accelerating the growth of cybercrime

Steven Kemp, David Buil-Gil and Yongyu Zeng are the team behind ‘CyberUp – Analysing the Growth in Cybercrime during COVID-19 and Post Pandemic Trends’, funded by the Research Collaboration Fund for Research Staff of the University of Manchester, which explores changes in digital everyday activities and opportunities for online crime during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Here, they consider the changing trends in cybercrime and what this means for policing.

How has the COVID-19 pandemic and its associated restrictions affected crime in the UK? And are these likely to be long-term changes or temporary fluctuations? Many sources have highlighted a drop in traditional street crime as a possible positive short-term consequence of lockdown measures; however, cyber-dependent crime and cyber-enabled fraud may be experiencing sustained growth that has been accelerated by the pandemic. This post provides a brief overview of what we know about the effect of COVID-19 on these two categories of cybercrimes in the UK, what we can expect for the future and how this may affect future policing.

Before moving on to the analysis of crime trends, let us quickly summarise how the pandemic and its associated restrictions may have impacted opportunities for cybercrime. This doesn’t require any great leaps; after all, everyone’s mobility and social interactions have been restricted to some degree with the various lockdowns and, as a result, activities such as work, leisure, dating, shopping, or banking, amongst others, have increasingly moved online. This shift was, of course, already occurring before the pandemic, but COVID-19 has served to accelerate the use of digital technologies for many daily activities. And the increases in activities like teleworking or shopping or online dating appear likely to endure. For example, many organisations have introduced permanent homeworking policies and there are clear changes in the business models of many high-street retailers. More people carrying out an increased number of online activities coupled with a reduction in activities in the physical space is likely to bring about changes in criminal opportunities. So how has all this impacted recorded cyber-dependent crime and cyber-enabled fraud in the last 18 months and what can we expect for the future?

Marked trends – and some interesting caveats

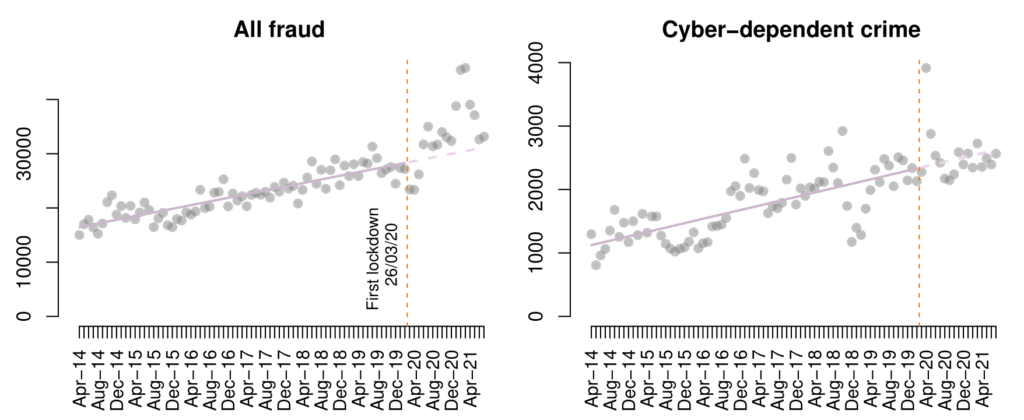

Our research on cybercrime and fraud in the first months of the pandemic revealed some marked trends and some interesting caveats. Using data obtained from victim reports to Action Fraud,we observed that total recorded cyber-dependent crime increased significantly in the first three months of the pandemic, but it subsequently dropped back to the pre-COVID rising trend when restrictions were eased, as shown in Figure 1. Similarly, though with a slight delay in comparison to cyber-dependent crime, recorded fraud also increased clearly beyond the forecast line in June and July 2020 and then bounced back towards the predicted upward trajectory in August.

We found evidence of online consumer fraud and cyber-enabled dating fraud remaining above the trend seen before the pandemic

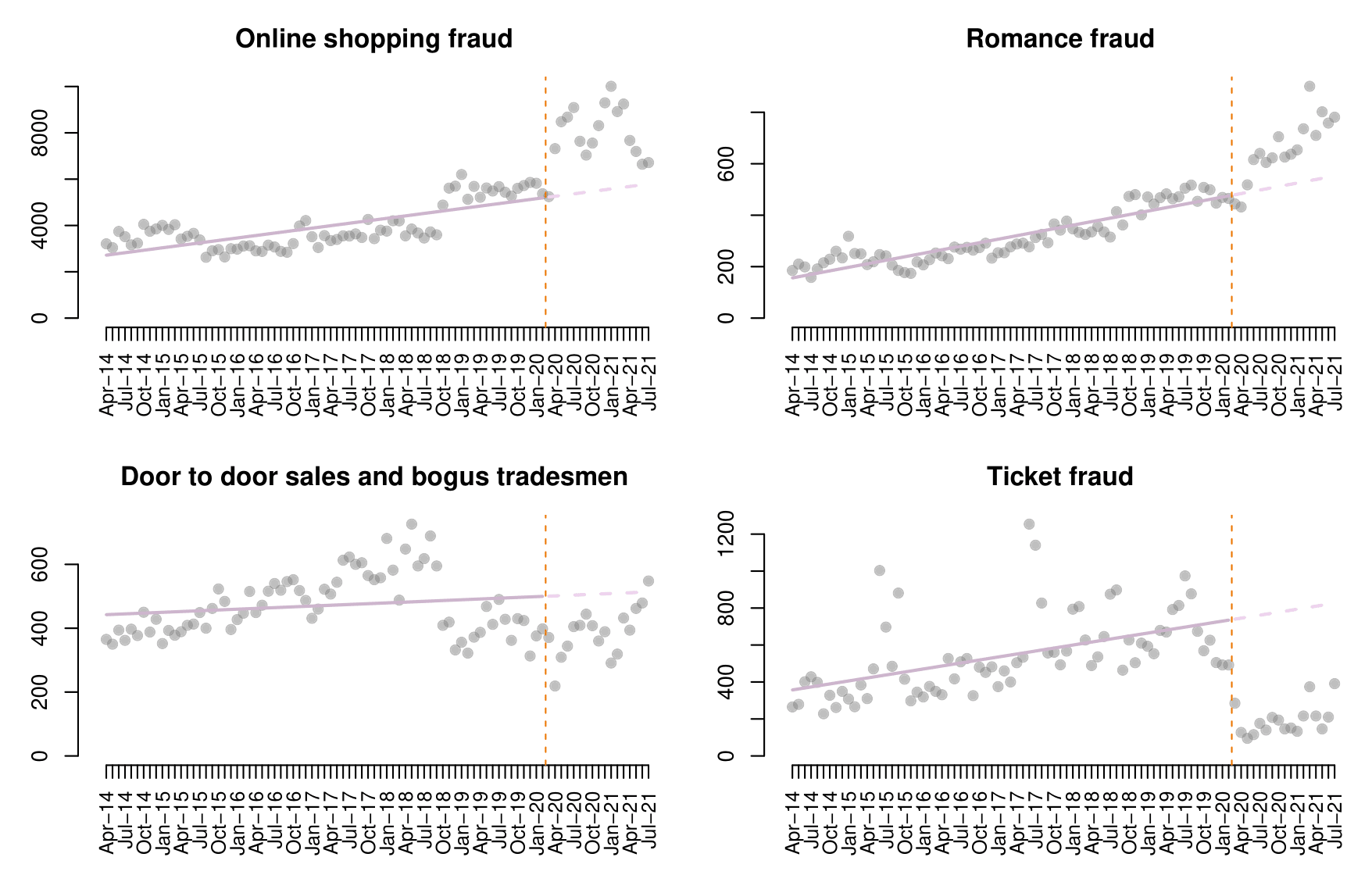

But the study of crime emphasises the importance of being crime specific, and our preliminary research on cybercrime and fraud at the beginning of the pandemic had previously revealed potential disparities between specific types of cybercrimes and between individual and organisational victims. In support of these preliminary findings, the time-series analysis up to July 2020 showed that, on the one hand, online shopping fraud and dating fraud rose considerably during the first months of the pandemic as these activities shifted from physical spaces to online spaces. On the other hand, ticket fraud virtually disappeared because, while it normally occurs online, it often depends on events taking place in the physical space. Worryingly, as shown in Figure 2, we found evidence of online consumer fraud and cyber-enabled dating fraud remaining above the trend seen before the pandemic, and later research identified a sustained rise in dating fraud up to the end of 2020. Regarding victims, our results showed that there were increases in reported cyber-dependent and cyber-enabled crime against individual victims but not against organisations.

Both online consumer fraud and cyber-dependent crime have stayed above pre-pandemic levels

To understand trends in cybercrime in the medium term and gain a better indication of potential long-term trends, we recently conducted a study of multiple lockdowns in Northern Ireland. We used data recorded by the Police Service of Northern Ireland between April 2015 and May 2021. The results show that both online consumer fraud and cyber-dependent crime have stayed above pre-pandemic levels throughout the pandemic. Moreover, we did not find evidence that the rates of these types of crimes will return to pre-pandemic levels, thereby making it increasingly important to monitor cybercrime trends during late 2021 and early 2022 to explore the possibility of a long-term increase in cybercrime. In contrast to these findings for cybercrime, in the same paper we also find that the reported rates of many types of traditional offline crimes, such as violence, drug crimes and theft from persons, have returned to levels seen before COVID-19.

The capacity of the police

In summary, evidence indicates that the criminal landscape is changing: many crimes with a cyber component, which were already rising before the pandemic, have experienced notable growth in the last 18 months and they don’t appear to be dropping back to the original pre-pandemic levels. Understanding these changes in crime is critical to the adaptability and the resource management of police forces in the post-lockdown period. This, in turn, underscores the need for reliable public data with which to analyse changes in offending, especially data on cyber-dependent and cyber-enabled crimes that occupy an increasingly larger proportion of criminal activity. Furthermore, increases in cybercrime raise questions about the capacity of the police to respond to the transformed criminal landscape. Research prior to the pandemic had already highlighted perceived weaknesses in training or policies and procedures with regard to cybercrime and online fraud. At a time when shifts in routine activities appear to be boosting cybercrime opportunities, it seems pertinent to re-evaluate current police responses to these crimes in order to protect public safety in post-lockdown UK.

0 Comments